Zero Day Growth Exploits

In the previous episode, I wrote about the best actions every marketer can take to grow their business. In short: cultivate true fans.

When you cultivate your true fans, your work is sustainable, life affirming, and your fans can actually return 10x more value than a regular customer because of the quality of their referrals (and the referrals from their referrals.)

When you don’t have outside funding, and your market will support more than one winner, this is the best classical strategy.

But what if you need to dominate your market?

Then you need zero day growth exploits.

In security, a zero-day is an undisclosed vulnerability that can be exploited by hackers to break into systems. While these holes remain unknown to the software vendors, there is a window where hackers can use them.

Zero-day vulnerabilities pop up all the time, and most major companies have teams dedicated just to find them. Many companies hire red teams to look for them, and the cloud supports dozens of security companies focused on protecting against this.

Security is not a solved problem, but vendors have skin in the game, so these vulnerabilities, once found, usually get patched quickly.

In marketing, there are similar opportunities that show up on a regular basis. These opportunities occur at the intersection of psychology and software.

Vendors often have no reason to close the vulnerability, so they often remain open indefinitely.

Most classic growth hacks were zero day vulnerabilities.

For example, AirBnB was able to exploit Craigslist to get customers to their site, eventually siphoning off traffic.

In the early days of Yelp, many companies legally copied their entire database of reviews and added it to their own site.

Speaking of Yelp, have you ever searched for a term and had Yelp show up in Google results, only to find the Yelp has nothing for you? They dynamically create pages to match search queries. Growth exploit.

Right now Instagram is a fantastic place to promote products, and it qualifies as a growth exploit because it wasn’t the intended purpose of Instagram, but its a lesser exploit because they will close it when it suits them.

Sometimes companies have a reason to close these vulnerabilities: Facebook, Google, Amazon, and LinkedIn have all made strong moves to shut down vulnerabilities, usually after the WSJ publishes an article about it.

For smaller platforms, however, closing these vulnerabilities is rarely a concern: there is no clear upside for them, and their own growth metrics can suffer.

Tumblr, for example, was a popular place to create free backlinks by making a dozen single page profiles. Tumblr had no reason to stop this: they could continue to flaunt impressive user numbers, ignoring that much of these numbers were not real people. Only when they got acquired, they started to clean up a bit and remove these inactive pages.

Twitter today is full of bots, but Twitter probably won’t close this vulnerability until the bots make them look bad. Maybe it already has: about 1/3 of Trump’s supporters in the last debate appear to have been bots.

Growth exploits are opposite of the network effect: they only work when fewer people use them. I’ll call this the arbitrage effect: when the benefit of a tactic is in inverse proportion to the number of times its used.

Most growth tactics, in sales and marketing, have the arbitrage effect: the more marketers use it, the less it works.

For a few years, the best marketers quietly used Hellobar and other popup tools to get email addresses with great success. Then SumoMe brought the concept to a larger market, only now it doesn’t really work.

Breakthrough Email is one of the best approaches to cold outbound email marketing - or it was, until the approach became common that your prospects likely ignore it.

This effect goes back to the early days of digital advertising: as Taylor Pearson mentions, the first banner ad had a 45,800% better conversion rate than the average ad now.

Even inbound marketing was a growth exploit: when HubSpot launched in 2006, ranking on Google was still as easy as publishing 300 word posts every day on different long tail keywords. But now that 1,000 plumbers write the same blog post, the value has shifted to other factors.

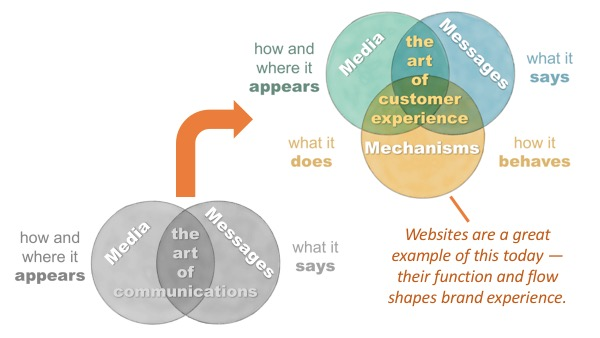

Is this just gimmick-based marketing? Well it is, in a way. Ad agencies have successfully used growth exploits for a century or more. The difference here is a shift in where the exploit occurs:

Ad agencies and PR mastered the vulnerabilities in the message and the medium: from the first jingle on radio to feminists lighting up cigarettes as “Torches of Freedom”, the magic was in this combination.

Mechanistic growth hacks represent a new trend: where medium and message could be easily copied once discovered, mechanisms are more easily obscured from imitators, and they don’t evenly distribute in the population.

So we can say that SEO is dead, mostly, but ranking a business on local search is still a relatively easy game.

The typical pattern seems to be the following:

- Zero day vulnerability gets created in the market

- Savvy explorers build crude tools to exploit vulnerability

- Vulnerability becomes less useful

- Savvy(ier) colonizers launch startups offering the exploit to everyone

- Vulnerability becomes less useful

- Hedgehog marketers begin preaching the gospel of the exploit

- Vulnerability is now basically useless

The value concentrates with the colonizers, with the explorers a distant second.

This isn’t new: this pattern occurred in the Gold Rush, and we still use the phrase “sell pickaxes to gold miners”: if you can’t get into a gold rush early, the next best move is to sell tools to the other latecomers.

If you can’t be the explorer, sell the gospel to the hedgehogs.

In tech, we’re still running the same playbook from 1849.

Does it have to be this way? Why does the pioneering gold miner tell everyone else about the gold he found? Why doesn’t that explorer quietly collect all the gold?

In 1849, that explorer needed startup capital. He needed the tools and the manpower to get to the gold. The inputs were linear to the output.

In 2016, this is no longer true: a growth explorer doesn’t need a lot of cash to build a massive exploit, just some imagination and products that can use it.

The constraint in 1849 was capital; the constraint today is time.

If you can’t move fast enough to use a zero day vulnerability, the next best option is to quickly adopt tools that are not yet mainstream. This is one advantage of a microservices martech model: by connecting multiple tools instead of one platform, you can move a bit faster and outrun the law of shitty clickthroughs.

Some of the exploits you’ll find if you adopt martech microservices:

- Faster page loads, ignored by most platforms, will give you an SEO advantage

- Reply rate tracking, ignored by most email marketers, is the missing ingredient in 1–1 emails that prospects actually engage with

- Sending emails by time zone can increase engagement if you target the right window

- Email courses work better than white papers

None of these confer huge advantages, anymore: they’ve been around long enough to lose some of their value. But if your competition uses standard Unicorn platforms, this small advantage might be enough.

Most modern marketers invest their time in just playing catch up: if they can just get their email marketing and social media integrated into one dashboard with a unified view of the customer, they think, their work is done.

For some marketers, in slow moving industries, this might be true.

For the rest of us, the real value of high growth marketing, the space where your leverage is 10x a Salesperson, is in finding these mechanistic zero day growth exploits, implementing them first, and then looking for the next one.

Its not easy, its not life affirming, but its the only way to grow fast.