Most successful businesses have a secret method to generate more profit than their competitors. In the age of the Internet, when everything you see can and will be copied, these secrets separate the businesses thriving from the businesses working twice as hard and still falling behind.

In this essay, I'll introduce a new concept that drives profit for many businesses, from retail grocery to B2B services. First, I'll explain the concepts of LTV and CAC, which you may already understand, and then look at the related mechanics that drive profitability.

A primer on LTV

LTV can be calculated in many ways, but generally speaking its the average revenue per customer over their lifespan.

Many people understand LTV in theory, but they never apply it to grow their business.

While it is important to know your LTV, the real gains occur when you know how to increase it.

For example, you might subsidize the equivalent of FedEx, Netflix, and Spotify for your customers:

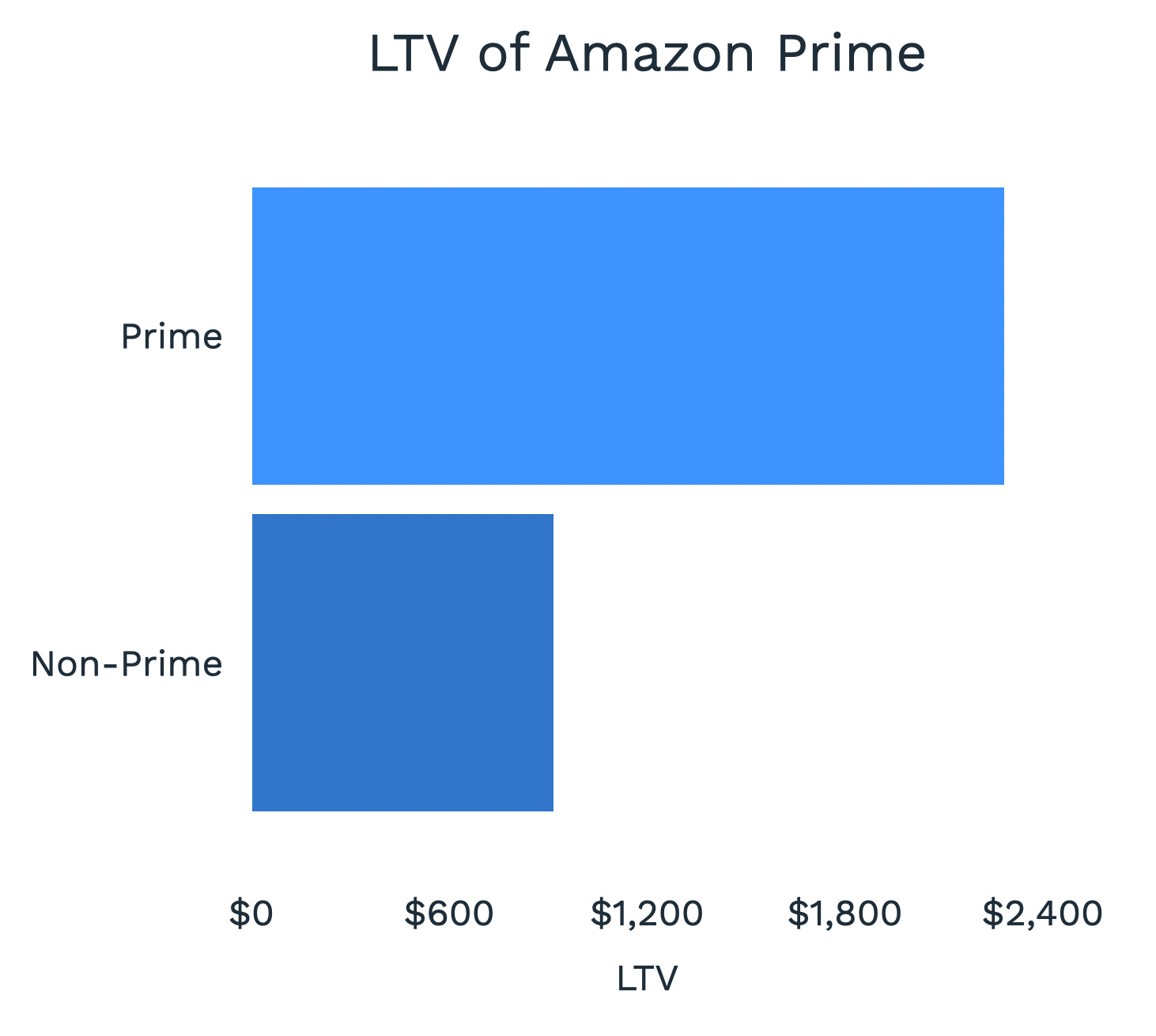

According to this research from Motley Fool, Amazon averages 2.5x more value from a customer subscribed to Prime than one who is not.

Now, most of you aren’t Jeff Bezos. Unfortunately, neither is the CEO of Target, who still (as of 2020) charges $5.99 for shipping.

When Amazon pays for shipping, starts a movie production company, and helps digital nomads start lifestyle businesses, they do it with the LTV in mind.

You can too.

Let’s consider an example from before the internet.

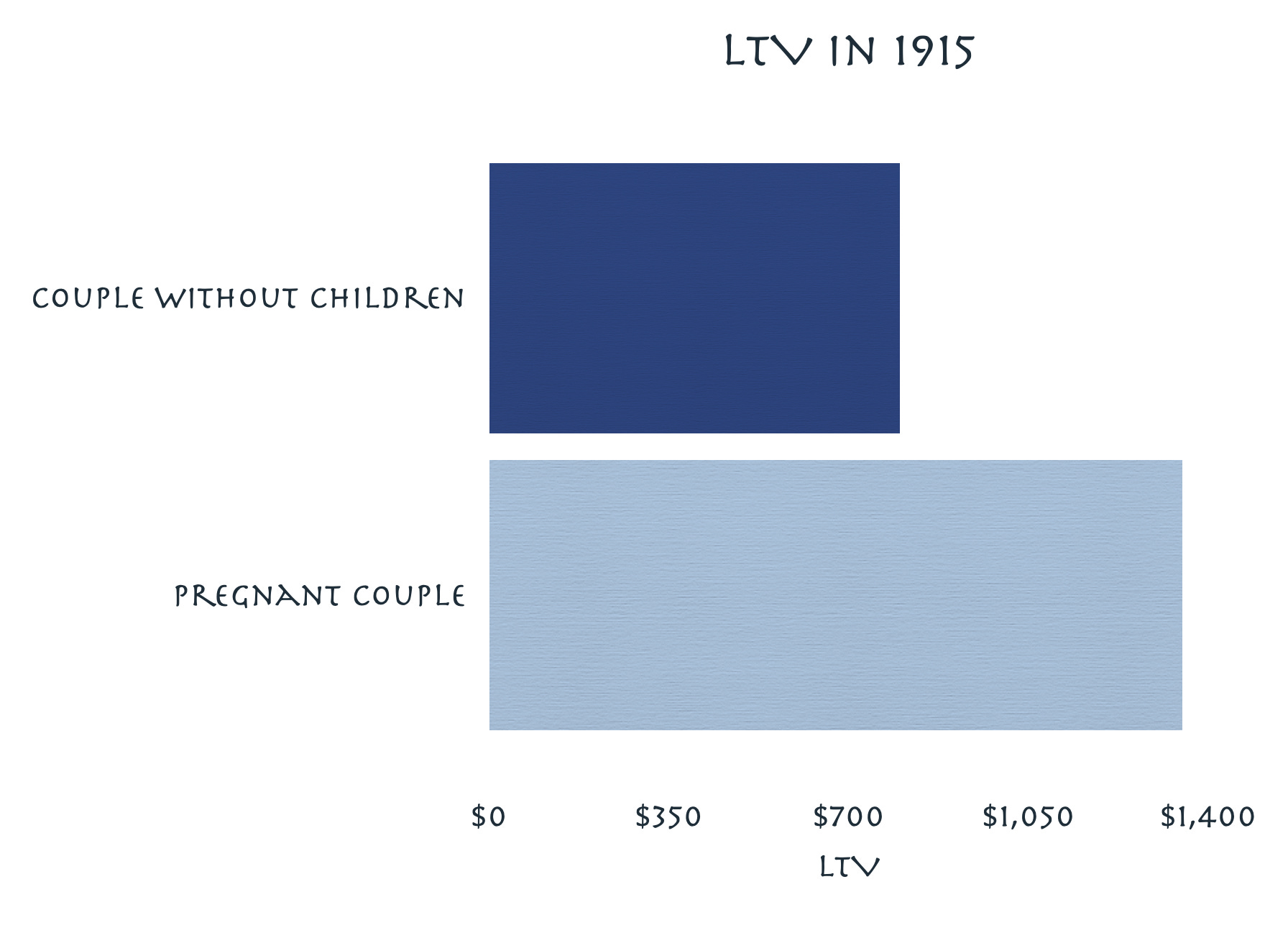

It’s 1915; you sell milk door to door. You know that most customers will continue buying for four years, at $50 per person per year.

Today you can choose between selling to a friendly couple who can’t have children, or to a pregnant couple who look like they’ll achieve the American Dream.

In Year 1, they buy the same amount of milk, but by Year 4 they are profoundly different customers:

While either couple could be expected to spend $800, the couple with 2.5 children will spend $1,350, nearly double the amount.

You sell milk; it doesn’t matter too much who buys it. All other things being equal, you’d be better off selling to the pregnant couple.

So the first step is to simply identify customers who will buy more, and focus your energy on those relationships.

Finding the hidden LTV

Actually, most milk salesmen would avoid both customers in the chart above; instead they would focus on selling to the households who already have 2.5 children, rather than seeking out the pregnant couple who will soon join them.

This is the transactional approach to LTV: selling to the customer who can buy the most now, rather than selling to the customer who can buy more later.

When you focus on the value at the moment of transaction, you end up with the most competition, because every other milk salesman is hunting for the same whale.

When you focus on the relationships, and begin with the LTV in mind, you actually end up selling to better customers, with less competition.

So the first thing you can do with LTV is find clusters of high LTV that your competition won’t see.

In over a decade building lead scoring models, I never had a client or colleague even suggest clustering around LTV. This is a major blindspot in B2B marketing right now, and a massive opportunity for the companies who see the whole value of a relationship rather than the transactional value of a contract.

Although buyer personas sometimes scratch the surface, they usually favor pop psychology over data modeling.

You can approach LTV like Amazon, and break out hard numbers; or, you can approach it conceptually, like a savvy 1915 milk salesman, and understand the trends that will change the market dynamics.

Either way, you will become more profitable than the copycats who mimic your website design but not your business model.

A primer on CAC

Now that you understand LTV, let's discuss CAC, and how you can use it to maneuver around your competition.

What is CAC?

CAC stands for Customer Acquisition Cost. As a marketer, you might measure this as the cost of the campaign that generated a lead; you would be wrong.

CAC is the entire cost of acquiring customers, divided by the total # of customers acquired.

Suppose you added 100 customers last year, and you paid $100k for sales and marketing. Your CAC is $1,000.

As a business owner, it is important to understand your CAC to make sure you don’t go broke selling to the wrong customers.

But generally the value in CAC is not in measuring it, but in understanding the options it gives you.

Returning to our example of Amazon Prime: Like Costco, Amazon knows their subscription membership actually increases LTV. This allows them to spend their CAC in creative ways that Target won’t try.

So you go to Costco, and you can get free samples of dozens of delicious foods, and then stop after at the gas station and get the lowest priced gas in your city.

You go to Amazon, and you get award winning movies and TV shows, exclusively on Amazon, for free.

Then you go to Target, and they want you to self checkout so they can reduce spend on minimum wage employees.

One of these is not like the other.

Don't Upsell; Upvalue

Costco and Amazon understand the power of CAC: it need not be spent on sales and marketing.

While Target spends their CAC on billboards and display ads, Costco and Amazon spend their CAC on improving the products and services they offer.

The same pattern occurs in most B2B businesses.

Many B2B companies can talk about their acquisition costs, but they focus on campaign attribution, first touch modeling, and ROI of marketing.

The slightly more advanced companies will think past this, and talk about ABM, how they flip the funnel, land and expand. This is better, but it misses the real opportunity.

When you focus on ABM, you hope that you can win by upselling.

But when you focus on LTV and CAC, you win by upvaluing.

When Amazon gives you free shipping, they upvalue. When Costco gives you free samples, or the best price on fuel, they upvalue.

Sometimes we upvalue by accident.

Marketing: truly great content marketing upvalues by improving the experience of your customers. Example: Josh Pigford writes for the Baremetrics blog and shares the real experience of his journey as a founder.

Product: often a product starts out by upvaluing, and becomes so valuable that others want to buy it. Example: Justin Mares built GiveLocal over 72 hours in March 2020 (and sold it one week later to USA Today.)

Selling: the best selling often occurs when you seek to help your customers rather than close a contract. Example: When I met my first client in Bangkok, I was genuinely interested in his business, not expecting to sell him anything. Result: easy sale.

Upvalue drives social capital

Upvalue does not mean free. When you give your product away for free, often it is because you don’t believe in its value, not because you seek to upvalue.

Upvalue is a Wow! moment in your product. Upvalue is the signal to your customers that you care about relationships more than transactions. Upvalue is the story that your product, already a good buy, will make your customer look even smarter a year from now.

You can actually profit more from upvaluing than upselling.

When you upsell, you spend some of your social capital (between you and your customer) to increase their contract size, so you can increase LTV.

There are ways to mitigate this extraction of social capital, but few salespeople do.

When you upvalue, you increase your social capital, and this decreases churn, which increases LTV.

There are many wrong ways to upsell, but you almost can’t upvalue the wrong way. So given the choice of increasing LTV through an upsell, or increasing LTV through upvalue, you should lean toward the upvalue whenever possible.

Mediocre businesses spend their CAC on acquisition costs, and hope they can make up for it through an upsell later.

Successful businesses spend their CAC on upvaluing, extend the LTV through retention, and only upsell when it benefits the customer.

To do otherwise would be to destroy your social capital.

Why does social capital matter?

The downstream impact of social capital and LTV

Run a business long enough you’ll know this well: referrals are your best source of new customers.

Referrals are not just great leads; referrals are buyers who already trust you. Referrals don’t send you an RFP; referrals buy lunch and tell you how to sell to them.

If you run a business, or manage your sales funnel, you know this well. What you may not know: referrals increase LTV.

How can a referral to a new customer increase the lifetime value of the referring customer?

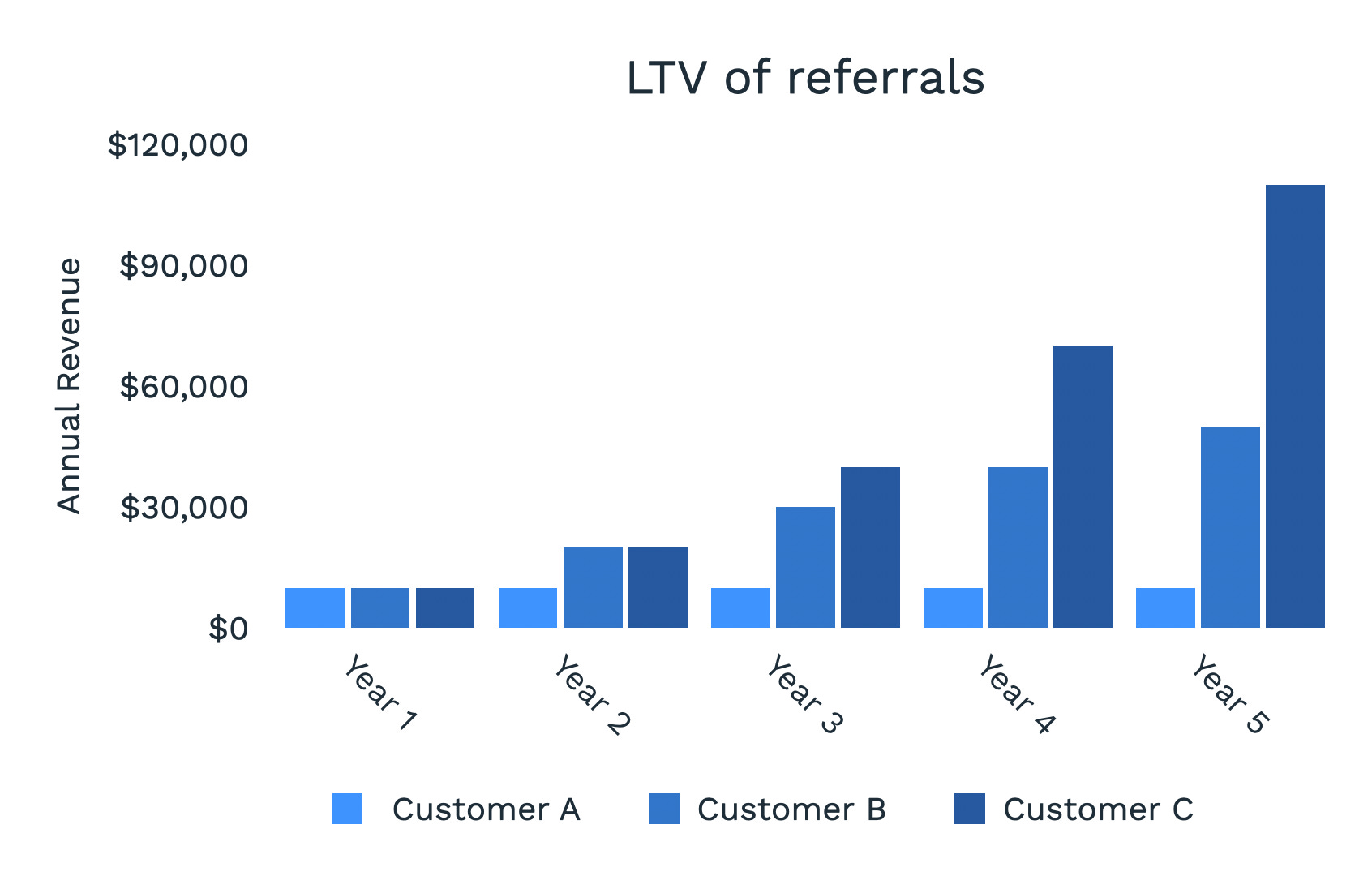

Imagine you could choose one of three customers to support for the next five years.

- Customer A buys $10k per year from you.

- Customer B buys $10k per year from you, and every year refers you to a new customer.

- Customer C buys $10k per year from you, and every year refers you to a new customer, who also makes one referral per year.

Which one do you invest in?

Over five years, customer A generates $50k. Customer B generates $150k.

Customer C generates $250k.

These are not just academic figures: these numbers can change your entire selling model.

In SaaS, the target comp for sales is 25 percent. So at $50k, your target cost of sales is $12k; you can barely afford an SDR to make calls, and every demo needs to be uniform. You have to automate everything, and hope you can spam your way to success.

At $150k, you can spend $37,500 to acquire the first customer; at this level, you can afford to hire professional closers. Every demo can be tailored to each buyer.

At $250k, you can spend $62,500 to acquire and keep that first customer.

These customers are buying the same product, but you can spend 5x more to acquire Customer C, if you can accurately predict they will bring 5x more in referrals.

That isn’t simply 5x more budget; that’s 5x more freedom than your competition.

Your competitors, oblivious to the LTV tree, will only be able to sell with a generic, junior sales team; meanwhile, you can afford to provide a white glove service that looks to outsiders like economic suicide.

Acquire ten customers like customer C, and you have an additional $500k to invest in a superior product and experience.

If you could invest $500k into your product to upvalue for your customers, what could you create?

- For $40k you can hire a ghostwriter to produce a book that defines your category and empowers your customers, then send them free copies to share with their network.

- For $60k you can produce an annual event where you celebrate customers, employees, and partners, introducing them to each other and solidifying the community.

- For $100k you can build a web app that complements your product, and give it away for free, increasing the budget your customers have for your core product. (What Joel Spolsky calls “commoditize your complement.”)

- For $250k you can hire an industry celebrity, on retainer, as an evangelist for your company.

Should you write a great book? Produce an epic event for your community? Build a free version of an adjacent product? Hire a celebrity evangelist?

If you can track your best referring customers, and acquire ten like Customer C, you’ll have budget to do all of these.

How to see the tree

Sure Steven, this sounds great in theory, but I can’t throw away money on the promise of more referrals.

I agree. If you sell a $10k ACV product, you should not start running an enterprise sales strategy tomorrow.

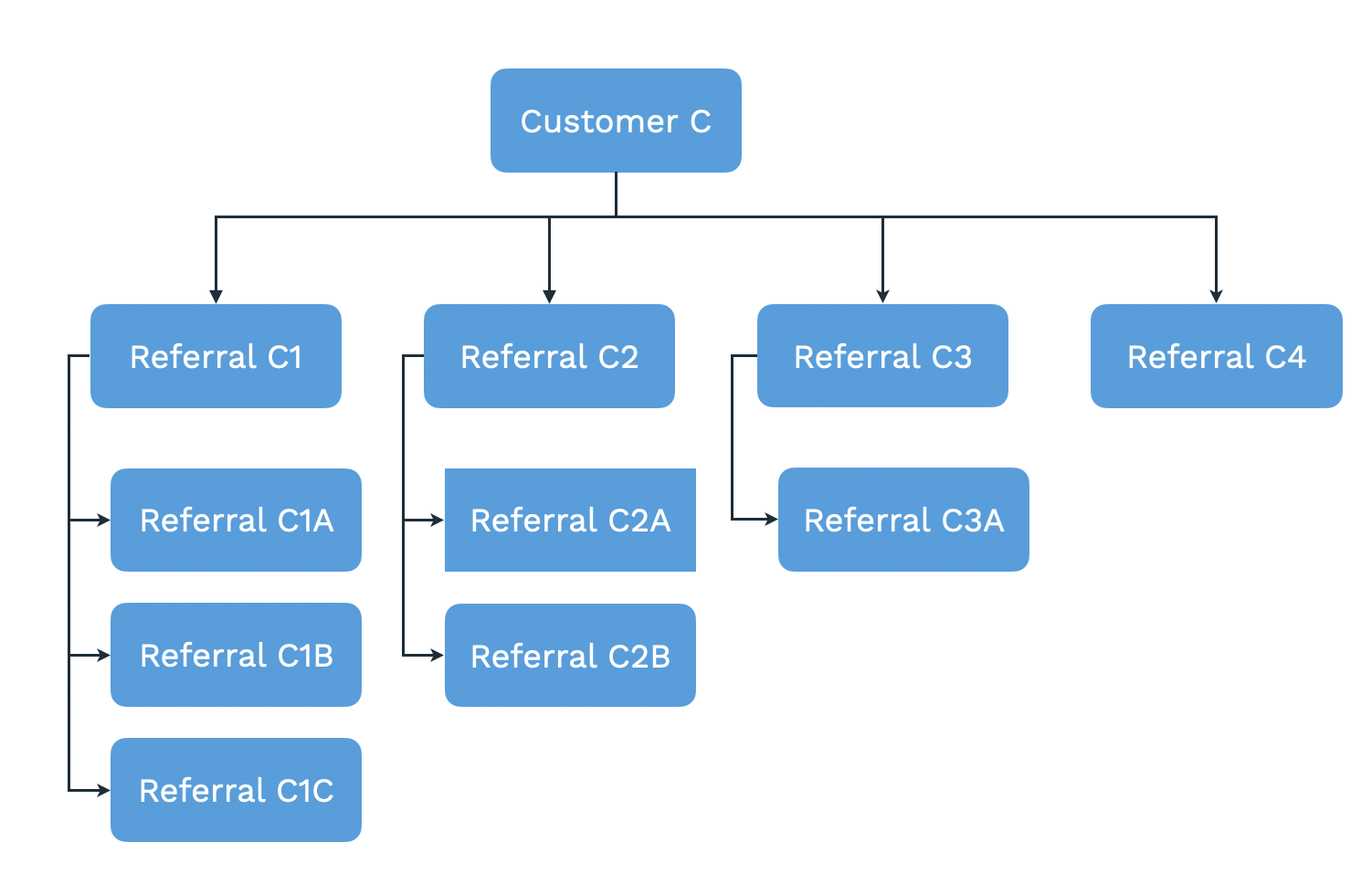

But you can start by measuring the LTV tree.

The LTV Tree reports on the actual revenue attributable to each customer or influencer. With an LTV Tree report, you can begin to see the value of referrals in general, and specific centers of influence overall.

How this report is actually implemented will vary in different companies. Some might try to get a granular weighting for soft influence like a published case study; some might apply this to partner marketing, where the actual value of these referrals leads to significant investment decisions.

No matter how you do it, you need to see past the current contract size, and understand the total value of your best customers. You need an intuition for which customers have the potential to be like customer C, and which customers can never surpass customer A, who is great for renewals but doesn’t help you grow.

If you started your week thinking a referral is worth $100 dollars, or your average cost per lead, and you end it understanding that a referral can actually be worth the accumulated profit of ten customers: this alone should fundamentally change how you approach customers and your business model.

Businesses who value a referral at $100 run social media contests.

Businesses who value a referral at the transactional cost of a client offer a 10% commission to anyone who refers them a deal.

Businesses who understand their LTV tree dynamics, who value that referral for its latent downstream potential, they can produce entirely new products and experiences for their audience.

Whether your business has the high profit margins of SaaS, the low margins of retail, or somewhere in between, you can leverage the LTV tree to model higher clusters of profit than your competition.