Don't start a business - start three

Why does the prolific blogger struggle to write a book over a decade, while his onetime intern quickly moves to publish a bestseller?

Why did the cofounders of Facebook have to persuade Zuckerberg to abandon his other projects?

How did Tim Ferriss move from author to angel investor to Oprah-level podcaster?

They didn’t let their project become sacred.

What is a sacred project?

A sacred project is a project enmeshed with your identity.

A sacred project is your first drawing as a child, which everyone adores because you made it.

A sacred project is choosing your college major like your life depends on it.

A sacred project is the PhD thesis that will finally allow you to be called a Doctor.

A sacred project is any project where you develop imposter syndrome. Indeed, fearing you are an imposter about to be discovered demonstrates something present that is sacred.

A sacred project is a project where the criticism of the project is indistinguishable from criticism of you.

If you can avoid it, don’t let your project become sacred.

Avoiding a sacred project is harder than it sounds. Here’s why.

Most of our society encourages us to become A-players, and tells entrepreneurs to only hire A-players.

What is an A-player, actually?

I used to think it was simply a high performing employee, but the same employee can have drastically different performance levels at different companies.

It turns out, performance is a lagging indicator of an A-player.

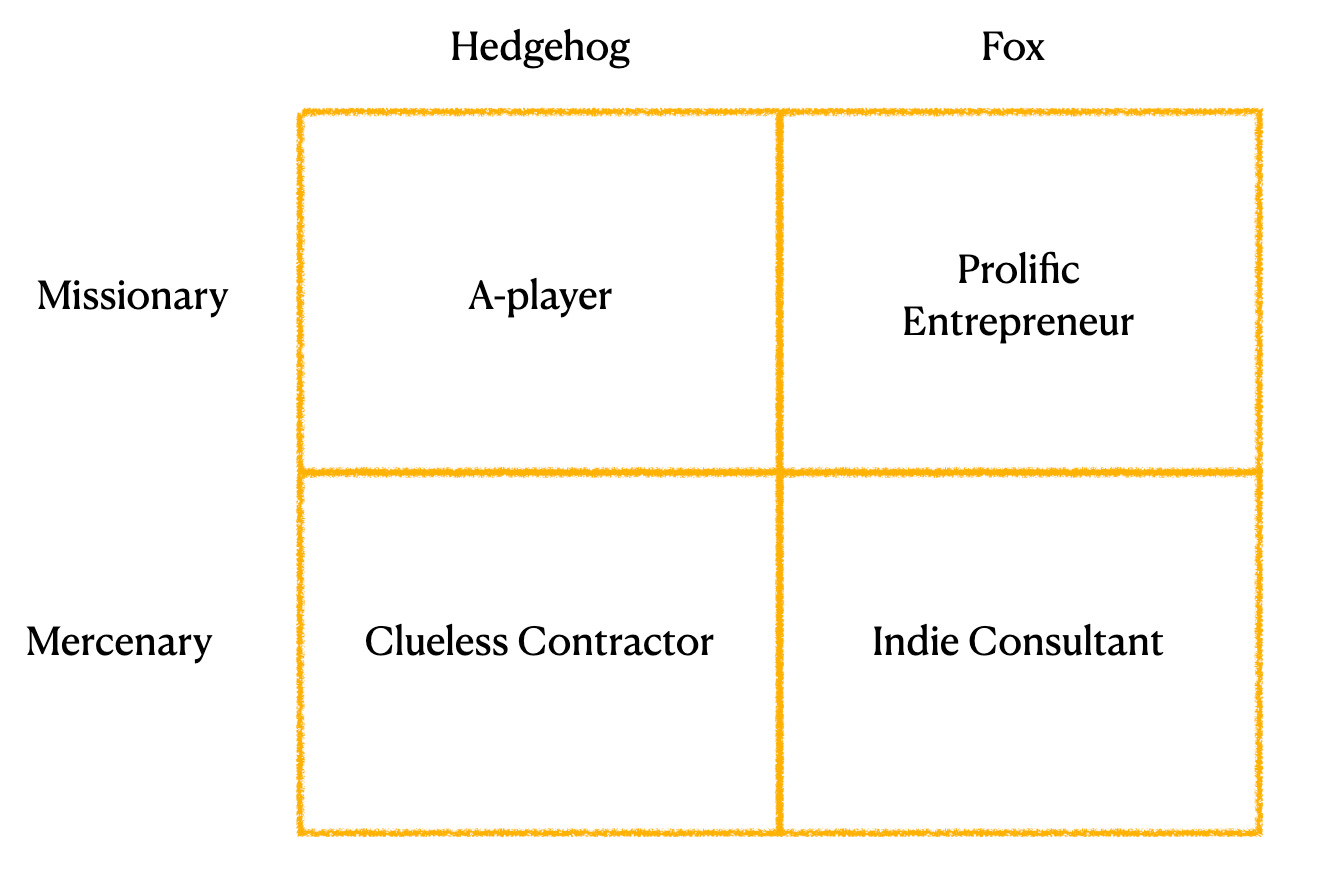

The leading indicators of an A-player seem to be missionary zeal and hedgehog mind.

A hedgehog, in the Isaiah Berlin sense, is a person who knows about one important thing.

A missionary is a person who has one purpose.

Combine the two, and you quickly get to a sacred identity that won’t allow criticism.

Prolific entrepreneurs often have missionary zeal, but they combine it with a foxy mind.

A missionary fox lives for a purpose beyond just making money, but they know there are many ways to achieve that purpose.

A missionary fox holds their purpose as sacred, but their means to achieve the purpose are flexible.

When a missionary fox succeeds, they might look like missionary hedgehogs. This is by design: to scale, they need to attract missionary hedgehogs to work for them.

Zuckerberg has created a culture where people unite to defeat Google, even though the project he started at Harvard was essentially a dating app.

Musk has created cultures where people work tirelessly to return to space or launch a new car, even though he spends his spare time writing white papers about the Hyperloop and starting The Boring Company.

Tim Ferriss wrote the book that launched a thousand lifestyle businesses, even as he was abandoning the digital nomad lifestyle to live in San Francisco and play a bigger game.

At some point, as you scale, you’ll need to appear to be a missionary hedgehog.

But not yet.

Before you’ve launched, before you have paying customers, before you have product market fit, you need to be a fox.

The easiest way to do this is the advice from the subject line:

Don’t start a business - start three.

When you start one business, everyone you speak to will treat it like the first artwork from a five year old: lots of empty oohs and aahs but no critical feedback.

You may not notice this, because you haven’t been five years old for awhile. So you’ll take the feedback and treat it like customer validation.

When you start one business, you might get lucky. Mozart, after all, was five when he shipped his first composition.

More likely, your best outcome is a quick failure, an end of runway and a return to a job where you can reboot and reorient.

The worse outcome, and more common, is a long slow failure, one where you burn not only two years of cash but also two years of feedback loops and social connection.

When you start three businesses, you sidestep all of this nonsense.

No longer will you implicitly ask your peers “do you like my first artwork?” Instead, you’ll ask “which one do you like the best?”

When you start one business, you avoid working on it by checking social media.

When you start three businesses, you avoid working on the first one by working on the second one.

When you start one business, you commit yourself to believing this is your best idea; if it fails, you are a failure.

When you start three businesses, you acknowledge that you don’t which idea is best, and a failure isn’t fatal. The only choice is to ship.

When you start one business, you risk two years of slow failure. When you start three businesses, you reduce your runway by two thirds, which is actually a good thing.

Failing fast and returning to employment is better than failing slow and becoming unemployable.

When you start one business, you’ve committed to this business as your thesis. A pivot means starting over.

When you start three businesses, you’ve committed to finding a synthesis. A failure of one means you’re closer to a success.

I use the word business here because it’s more accessible, but unless you’re Elon Musk or Jack Dorsey, you probably won’t commit to execute on three businesses.

Before you run out and order three new articles of incorporation, consider that the precursor to a business is a project.

A new project attracts feedback that a new business never will.

When you tell peers you’ve started three businesses, you’ll lose their attention because this doesn’t match their worldview.

When you tell peers, you’ve started three projects, they’ll be open to hearing about them and providing critical feedback.

That’s all I have to share on this right now.

If you’re on the verge of starting a business, and you want to start three projects instead, shoot me an email and I’ll give you an email template and a specific tactic you can use to get better customer validation.