The Da Vinci Pattern

a Florentine, a Brit, and a Dutchman walk into a profitable bar

How did Leonardo Da Vinci transcend three generations of notaries to become a famous artist, military engineer and scientist?

How did Charlie Chaplin become the first great movie star, and the most famous person on the planet?

How did Pieter Levels build his digital business to $1M in run rate even as his website was relentlessly scraped and copied (and a funded competitor failed)?

They all discovered unique abundance.

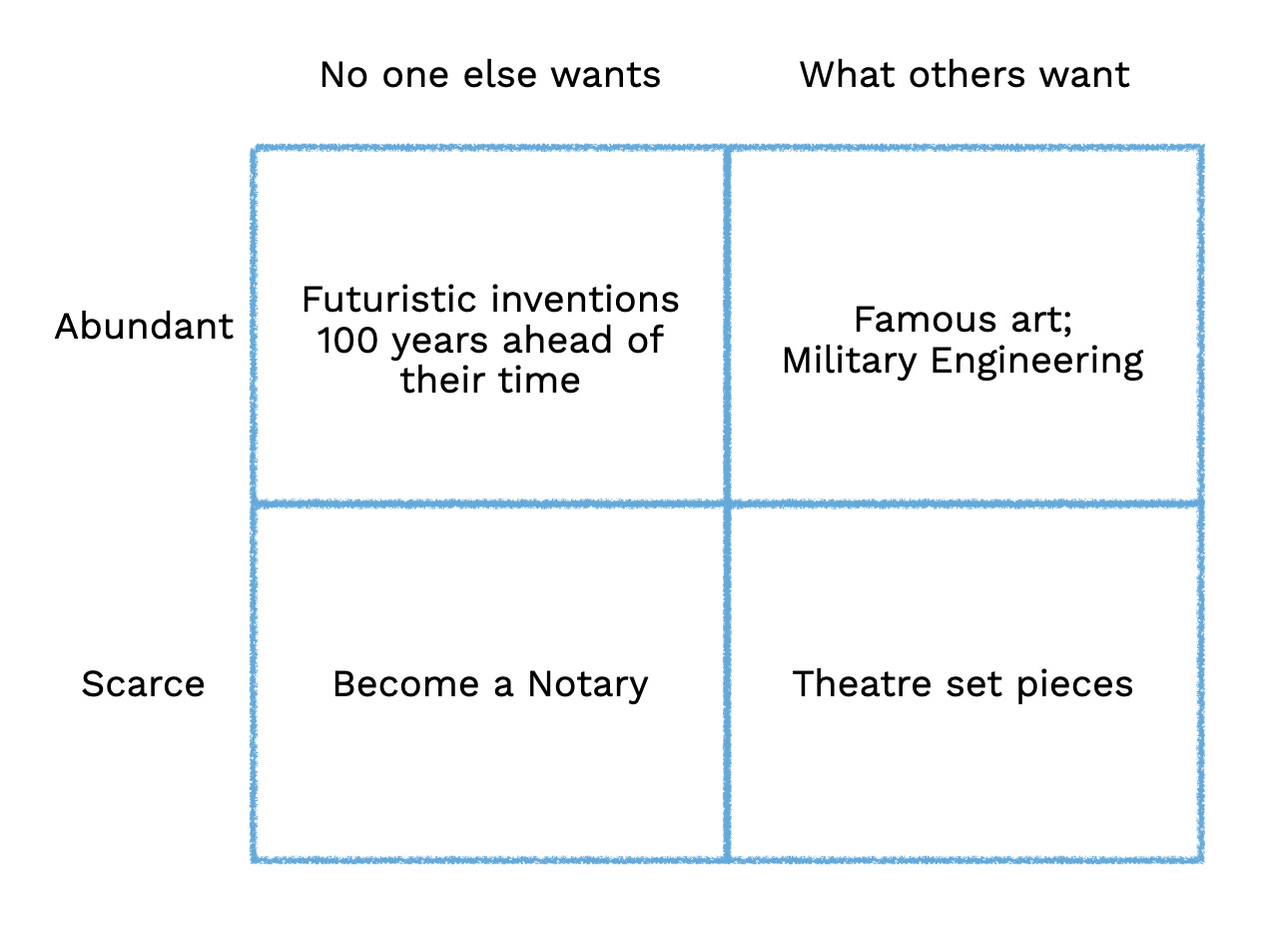

As a child, Da Vinci was on the path to become a Notary, following the footsteps of three generations. Although his note taking skills would make an exceptional archive of his life, circumstances and personality allowed him to forge a path distinct from his parents, and he became an art apprentice instead at a young age.

Working as an artist, he made a lot of his income from creating theatre set pieces, none of which would survive. Seen as an artist and a musician, he wanted to be known as an engineer, and at thirty he relocated to Milan with the intention to become an engineer.

His engineering ideas were fantastic, in every sense of the word. He invented the helicopter, scuba gear, solar power, and so many more. Most of these ideas were at best ahead of their time, and at worst an abject failure in his time, such as redirecting the Arno River to deprive Pisa of water.

Yet his work endured in his art and his research, producing Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, as well as the first weaponized maps.

Like many, Da Vinci started with the path of work that he wasn’t good at and no one really wanted him to do (except perhaps a few family members.) Fortunately for him, this script was not strong enough to hold, and he was able to find a craft he enjoyed more.

Although great at art, this doesn’t seem to be the path he saw for himself. His contemporaries argued that painting was a mechanical art rather than a liberal art, and he wasn’t driven by the money that came from producing portraits for aristocrats.

After toiling in work where he wasn’t unique, he shifted focus to work that was more abundant for him, exploring science and inventing new machines.

Eventually he found synthesis in much of the work we know him for today. Although his understanding of anatomy and physics were on their own superfluous, applied to the Mona Lisa, we see movement in a portrait.

Although many machines he designed were impractical, his pedometer allowed for a precise kind of map that would enable far great military successes to the user.

Once he had the luxury of pursuing his own abundance, Da Vinci stopped painting portraits of the wealthy and continued focusing on his abundant interests.

Centuries later, Chaplin’s story rhymes.

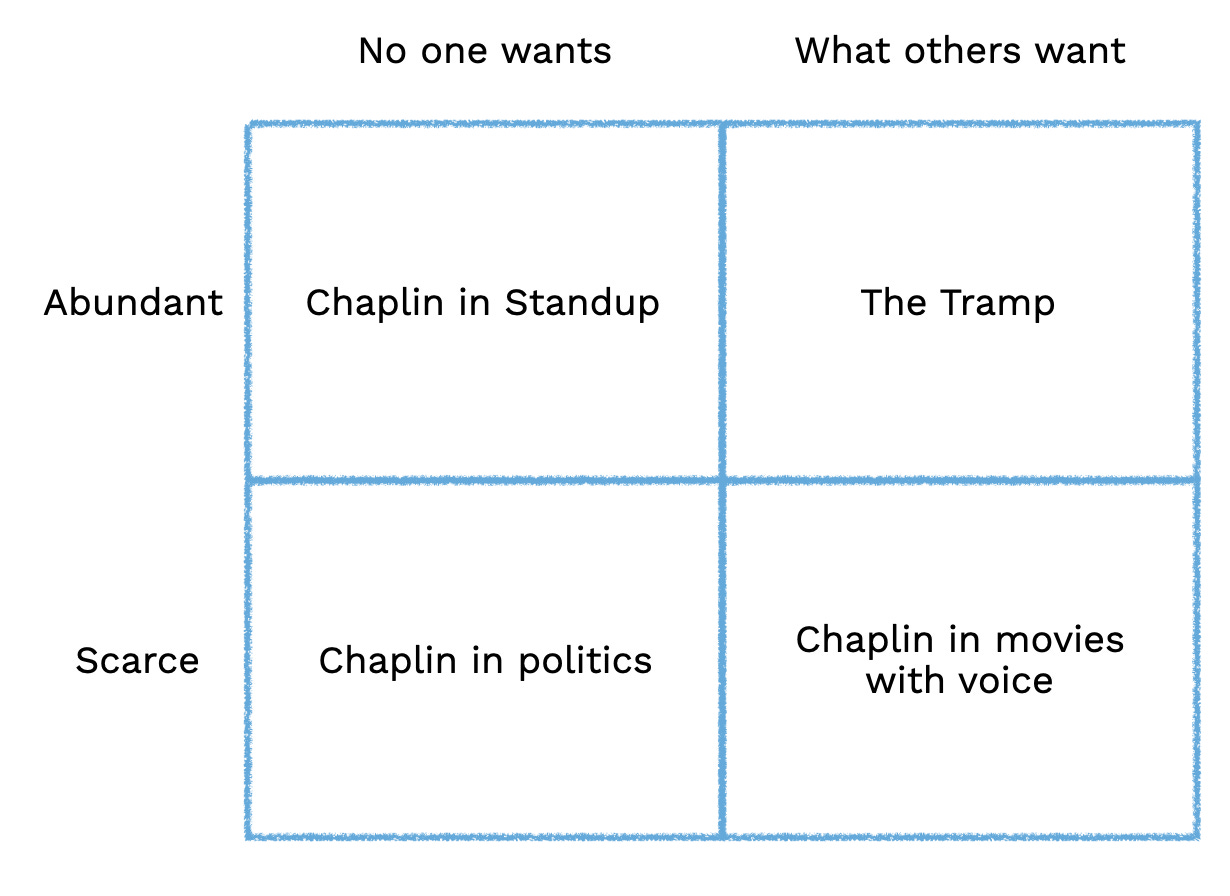

Born in poverty, Charlie Chaplin made his stage debut at age five, and dedicated himself to acting by 14. Along the way, he found some success in vaudeville, and some failure in standup comedy.

Buoyed by the wave of technology, Chaplin was already known, but he reached Da Vinci levels when he produced movies with The Tramp.

Watching Chaplin’s movies today, what stands out is the intense emotions, all the more incredible when you consider he produced and directed nearly every film and his cast often had no experience acting. I recommend “City Lights” for emotions and “Modern Times” for great satire.

Later, Chaplin would get in trouble for trying to involve himself in politics (which it seems almost no one wanted least of all him), and largely resisted the public’s demand that he star in movies with voices.

But by then the fortune was made: Chaplin had found abundance in making what others wanted, and only pride and hubris kept him in the game.

You probably don’t know Pieter Levels.

Among a certain crowd of entrepreneur, Pieter is a hero.

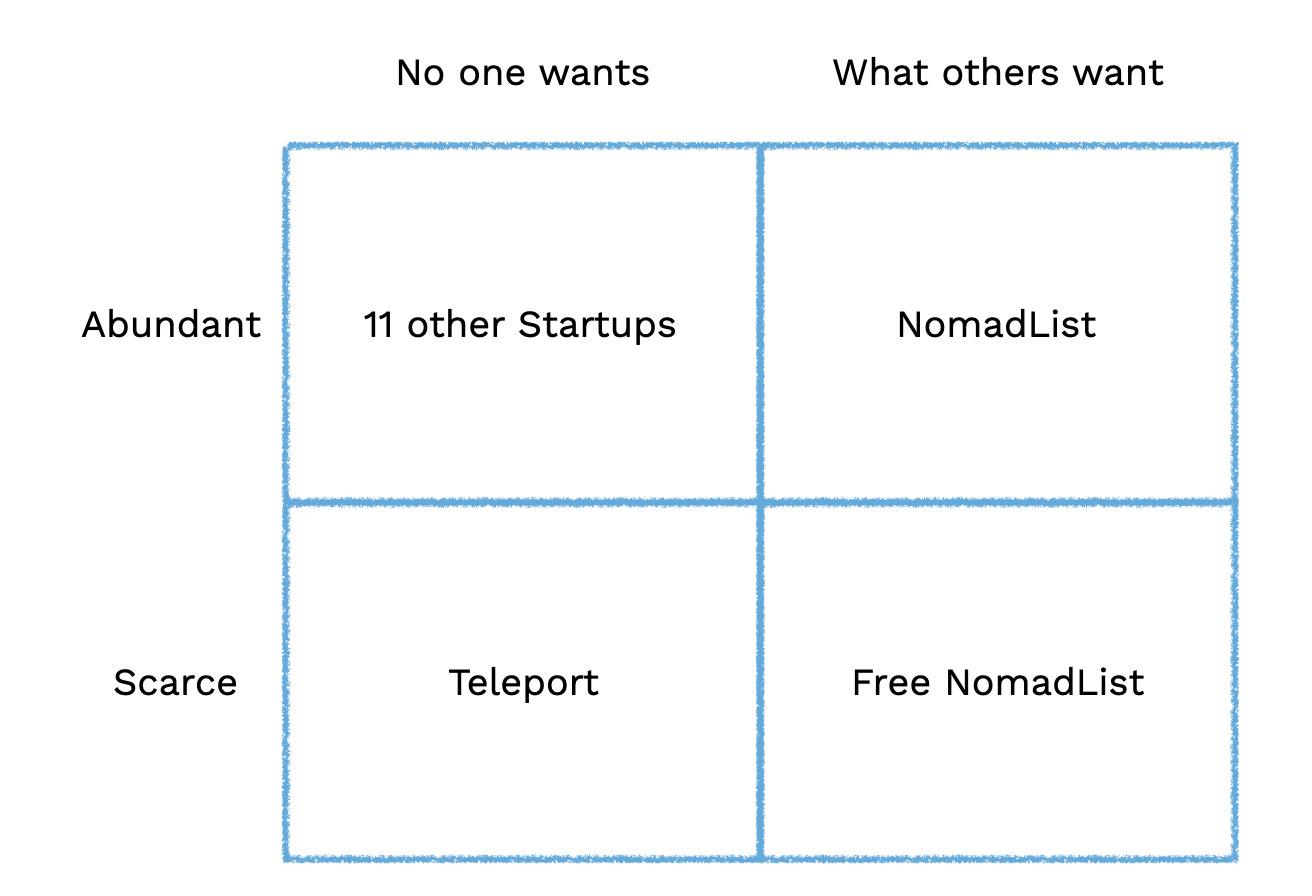

In 2014, Levels called his shot, committing to start 12 startups in 12 months.

Four years later, he reached $1M in run rate, largely from the business of NomadList.

The same year he started, Teleport was founded to do largely the same thing: provide a comprehensive look at different cities for the global entrepreneur.

Teleport was acquired for an undisclosed amount, while NomadList continues to grow.

I don’t know Pieter’s story, but the pattern emerges again:

While Teleport sought out seed funding and tried to make a large business, they were forced into a model that catered to corporate expense management - not something anyone particularly wants, nor abundant.

Meanwhile, Levels solved the classic programmer problem by creating abundance. Where others like Teleport only had one product, and never quite found what the market wanted, Levels created a dozen projects and found what others wanted through seeing what they paid for.

He briefly tried to make NomadList free, but the support costs created a new scarcity, his time, so he returned to the formula that proved abundant.

Three stories; three centuries; three successes.

What do you have in abundance that others want?

Let’s find that.