How to set better business goals

Three alternatives to OKRs

Three alternatives to OKRs

As an entrepreneur, one challenge I’ve struggled with is motivating my employees. How do you get others to work as hard as you do?

Desperate, I read everything I could and tried different approaches. Benioff’s V2MOM, Google’s OKRs, Empathetic 1–1s, nothing seemed to work.

My fundamental mistake, and probably the mistake you’re making as a manager: applying the same motivational criteria to every employee.

Instead of a one size fits all approach, you need to consider the factors that lead to this employee working for you, and then set the rules of the game to match the game they want to play.

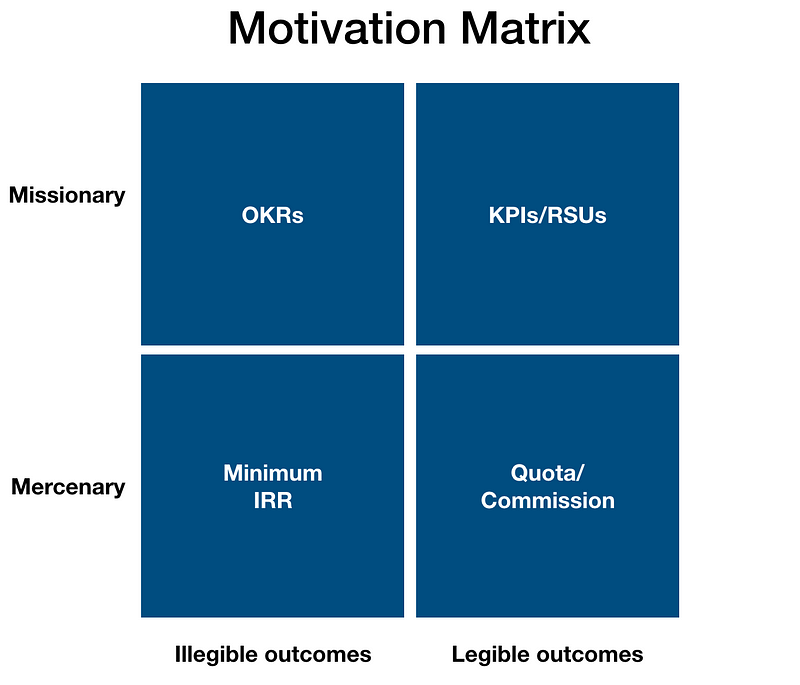

There are two questions to answer here to determine the right motivation.

Is your employee a missionary or a mercenary?

Mercenaries work for money, missionaries work for meaning.

As a boss, we all hope to have missionaries, because they seem to do more. Extra hours, recruiting for the company, retweeting our company posts: these are the amenities of hiring a missionary.

Unfortunately, your company probably hasn’t earned missionaries. The number of people who get excited about changing the future of IT repair is… small.

Here’s a quick test to determine if you can attract missionaries:

- Do strangers volunteer their time to contribute to your cause?

- Do students dedicate their degree to your industry even though it makes for a bad career choice, financially?

- Do you have a famous company culture?

- Are you a non profit?

- Do you save lives?

- Do you have a company ikigai, a purpose beyond growing and winning a market? Is it unique or the same as every other company?

If you answered no to all of these, you won’t attract missionaries, except for the occasional clueless.

That brings us to our second question.

Does your employee have legible or illegible outcomes?

With the explosion of data, we’re going through a quiet revolution in business, where every department is attempting to demonstrate ROI.

This seems useful, at first glance, but it predictably fails in many instances. The problem is legibility.

A salesperson, tasked with making 200 calls per week and setting 10 appointments, has high legibility. They truly play in a “numbers game” and they can leave early Friday afternoon knowing they hit their numbers.

A marketer, tasked with increasing brand awareness, has no such legibility. How do you accurately measure the mindshare of your brand and its impact on future revenue? You don’t.

Sometimes the same profession can be legible in one area and illegible in another.

A personal injury lawyer has a high legibility: they know they will win or settle x number of cases for y% of the initial ask.

A corporate attorney, charged with protecting the company’s IP, will have no such legibility.

Consultants are an interesting outlier.

An IP attorney working in-house doesn’t have legibility. That same attorney, working for a firm, is measured on billable hours.

At first glance, it seems most companies in-source illegible work, and outsource legible work. I’m not sure why (though Taleb’s Slave theory applies), but the primary job of most consultants or freelancers seems to be solving legible problems.

So most of your employees will work in illegible problems.

Quick test to tell if a problem space is legible or illegible:

- Would you bet your job on increasing the outcomes by 10% next quarter? (most legible outcomes are also linear in growth)

- Are the measures for success standard in your profession?

- Are there many freelancers or consultants delivering your exact work output?

If the answers to all of the above are yes, you probably have a legible outcome.

With these answers, you can finally provide the right motivation for your staff.

Here are some typical examples.

Missionary with legible outcomes

This is the rarest type: someone who works for a company with a real mission (not just a mission statement) and legible outcomes.

The most typical example here is a salesperson for a disruptive startup. You know that making 500 calls will, on average, generate one new sale. And the purpose of the company aligns with your own values. Every call you make reinforces your own meaning.

This person should be measured on KPIs (likely industry norms) and paid in stock. They may want commission as well, but the stock will be worth more to them personally, and reinforce their purpose.

Another example: you work for a law firm dedicated to class action lawsuits against businesses destroying the environment. Think the story of “A Civil Action.”

You’ll probably be measured on billable hours, but most of your compensation should be in some kind of equity or shares. You could take a percentage of your wins, as well, but that will be less interesting to you.

Mercenary with legible outcomes

Next we have the legible mercenary.

This is the first VP of Sales in a B2B startup: someone who immediately brings relationships that will open doors and close deals.

This is the growth hacker, charged with increasing addiction to your app and lowering churn to hit targets for your Series B.

You likely want to pay this person in stock, and they’ll accept some of it, but their existence is based on making money, not meaning. You’ll pay dearly, and it will be worth it.

This is Saul Goodman suing on behalf of the elderly. This is the freelance chemist who saves the paint company $5M, in one day, by making a tiny change in their chemical composition. This is everyone who charges value based pricing.

Most of your consultants, those who you’d never make a job offer full time, because their skill is so specific, they fall in this category.

You might pay them in stock, or retainer, or any other manner, but their motivation will come from the commission, from the immediate share of their success.

Mercenary with illegible outcomes

Next we have the illegible mercenary.

The illegible mercenary is likely your most common employee.

This is the manager who stays in a job they hate, because of their mortgage.

This is the in-house accountant who obliges to work 80 hour weeks every Q1 and dreams of leaving.

This is the VA who works Sundays despite their religious beliefs.

In most cases, the illegible mercenary is playing defense: they simply want to keep their job.

Over time, some of these mercenaries will become missionaries: they find meaning in their company, and start saying things like “I can’t leave, I have such great friends there.”

As a manager, one of your goals is to convert mercenaries to missionaries, but until then, the best way to motivate them is to provide an understanding of the minimum expected of them.

Google does this extraordinarily well: they tend to hire the smartest possible people to do the smallest possible tasks. In doing so, they set the minimum bar incredibly low for a group that is used to hitting the highest targets.

As a result, the biggest complaint from Google employees I’ve heard is the low level of expectations. This seems to act as a sorting mechanism: some leave to start their own company, some develop side projects that turn into Google products, some flock to teams where they have a higher purpose.

If most of Google’s employees start out as mercenaries, its safe to say yours are too.

If your employee is a mercenary, with an illegible work outcome, the best thing you can do is provide this minimum expectation to keep their job. When you set goals, set the bar low and make it clear who gets fired.

In return, they’ll spend less time trying to read your mind, and more time doing their work.

Missionary with illegible outcomes

The final type is the missionary with illegible outcomes.

This group is the one we hear most about in the startup content bubble: employees who have no legible contribution to their company, but they believe in it and will do whatever it takes to help it succeed.

With this group, OKRs are perfect: they allow you to inspire them by imagining higher goals then they think they can achieve.

For missionaries, achieving these higher goals reinforces their purpose at the company and binds them to the company.

For the company, achieving these higher goals applies Roman engineering to your outcomes. In other words, if you don’t know whether you need to deliver 2 features or 20 features in your next release to appeal to your market, inspiring your team to deliver 20 features will increase the likelihood of your higher level outcome.

Illegible missionaries find meaning in their employment, and they’ll give 110% just for the sake of this meaning.

Like this post? Give it a clap for every employee or contractor you’ve incentivized the wrong way.